As someone who often works on my illustrations in public spaces—whether it’s my local café, an airport lounge, or mid-journey on a train—I’ve come to expect a certain kind of conversation. People spot the sketchbook, the watercolours, the characters taking shape, and inevitably ask:

“Are you working on a book?”

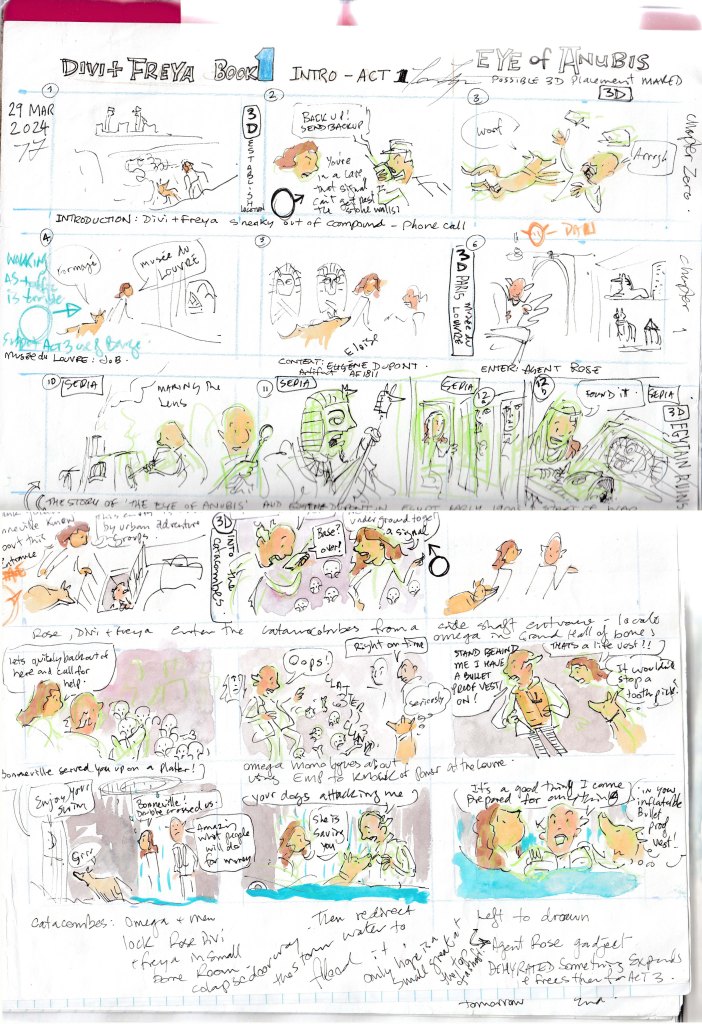

Sketching on a train (2024) while travelling in England

When I say yes—usually a graphic novel or picture book—the next line is almost always:

“I have an idea for a book!”

What follows is often an enthusiastic elevator pitch. Sometimes it’s a heartfelt personal story, sometimes a quirky concept with a twist ending. Occasionally, it’s accompanied by a generous offer: “If you like the idea, maybe you could illustrate it?” or “Could you take it to your publisher?”

I always appreciate the passion and creativity behind these moments. But I often have to explain that this isn’t how the publishing industry works. Generally, publishers prefer to pair a manuscript with an illustrator they believe can bring the text to life visually. They’re usually hesitant to take on projects from first-time authors and illustrators working together, as it can reduce the chances of the story being accepted.

So here’s the advice I always offer:

As interesting as a story idea may be, it’s not a story for publishing until you write it down.

Ideas are wonderful. They’re the spark. But they’re not the fire. A story doesn’t leap from your imagination to a printed book without that essential step: writing.

Tip 1: Start Writing

After talking with many authors and illustrators, it’s clear there’s no single “right” way to write. We’re all wired differently, and what works for one person might not work for another. But if you’re staring down a blank page and wondering how to begin, here are a few things I’ve found genuinely helpful:

- Just start.

Don’t wait for the perfect sentence or a fully formed plot. Begin with whatever’s in your head and let the words flow. - Forget the rules.

Grammar, spelling, structure—none of that matters in the first draft. Your only job is to get ideas down. - Write without judgement.

Don’t worry about whether it’s “good.” Just write. The more you do, the more you’ll discover what your story wants to be.

It’s okay to be messy. This is writing for your eyes only.

Back at uni, the HDR team used to run a session for master’s and PhD candidates called “Shut Up and Write.” And honestly, it’s great advice. Here’s how it works:

- Set aside one hour of your day

- Turn off distractions—no emails, no social media

- Set a stopwatch for 15 minutes

- Write like mad for those 15 minutes

- Take a 5-minute break

- Repeat the cycle three times

At the end of the hour, you’ll have a bunch of ideas written down. Some might go nowhere. Others might be the seed of something brilliant. Either way, you’ve started—and that’s the most important part.

Tip 2: Find Time and Build a Routine

I start every day with a coffee (or two) in one of my local cafés and draw for at least an hour. Throughout the day, I look for pockets of time that would otherwise be wasted—sitting in a waiting room, waiting for a bus. These are perfect moments to pull out a notebook or sketchbook and scribble for five minutes.

The simplest way to do this? Swap your phone scrolling time for scribbling time—or at least cut the phone time in half. You’ll be surprised how much you get done.

Tip 3: Match the Space to the Task

Not all writing time is about crafting perfect words. Different parts of the process need different environments.

I can work on rough sketches and notes anywhere. I always carry a sketchbook and plan travel sketchbooks to keep ideas from each trip in one place. But when I’m working through a manuscript and need to concentrate, I often wear noise-cancelling headphones at the café or work from home when it’s quiet.

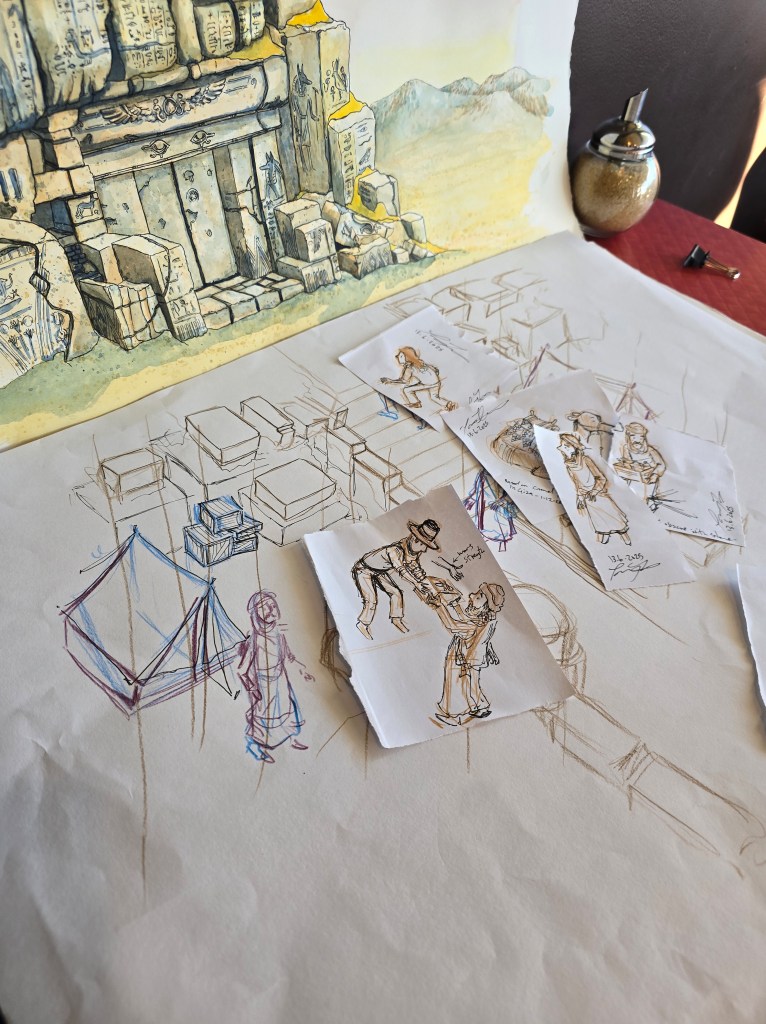

Once the planning is done, I can work on final illustrations anywhere with enough space. I choose cafés where I’m less likely to be bumped or where the tables are large enough—especially when working on large-format illustrations.

Tip 4: Shaping a Story Is a Process

You don’t sit down and write a finished novel or picture book from the start. You’re beginning a process. Everyone writes differently, so it’s important to find what works for you.

Here’s What Works for Me

Personally, I use a mix of sketches, rough story maps, character designs, and text to generate a story. It’s not a neat, linear process. I jump between these tools as needed, letting the story evolve organically. Sometimes a character sketch sparks a plot twist. Other times, a rough map of the story arc helps me refine a visual moment.

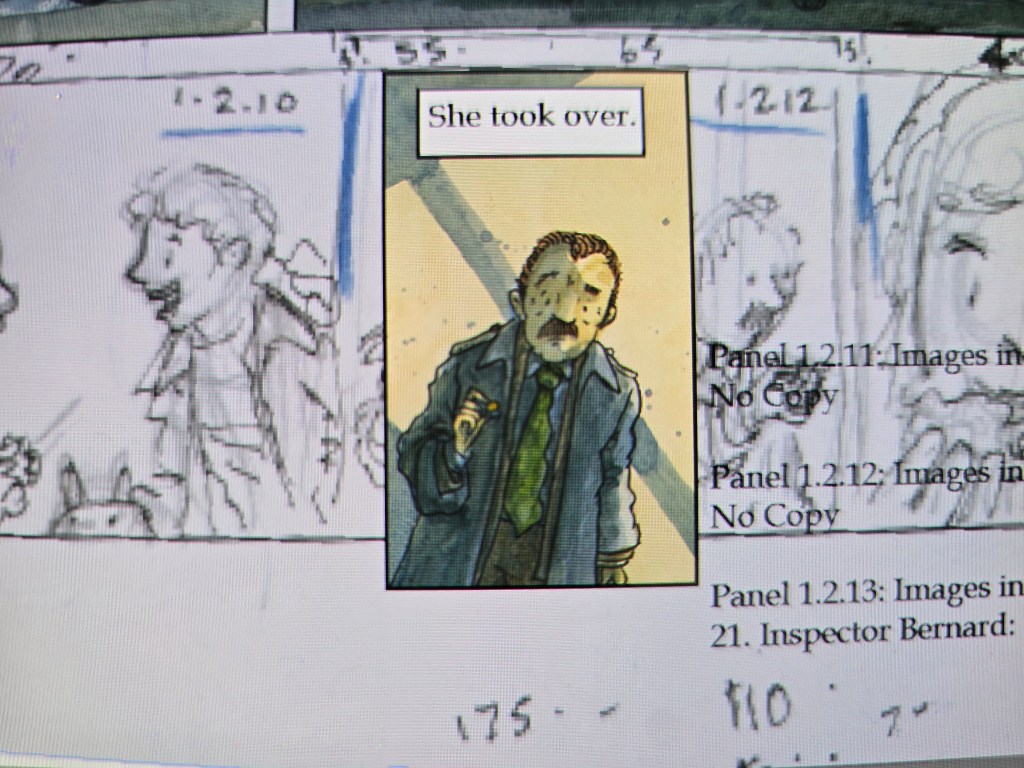

Eventually, I need to bring it all together—especially when it’s time to present the idea to a publisher or plan it out for a book format. That’s when I shift into layout mode. I create storyboards and rough page designs to explore how the images and text will interact. I ask myself:

- How do the images work together to form a visual narrative?

- How do they flow across a page and through the structure of a book?

- Where does the reader pause, turn, or feel something shift?

This is where the story starts to take shape—not just as a collection of ideas, but as a cohesive experience for the reader. It’s a dance between words and pictures, rhythm and pacing, emotion and clarity.

Stories Are Everywhere—But They Need You to Write Them

I love these spontaneous conversations with strangers. They remind me that storytelling is alive and well, bubbling just beneath the surface in everyday life. But if you want your story to grow beyond an idea—if you want it to live in the hands of readers—it starts with writing it down.

So next time inspiration strikes, don’t just tell someone about it. Grab a notebook, open a document, or sketch out your thoughts. That’s where the real journey begins.

Leave a comment